Lamborghini Gallardo LP 560-4 Spyder gets a facelift for 2013

For 2013, changes to the Aventador's little brother are skin deep. What enthusiasts really want is an all-new Gallardo that can take on Ferrari and McLaren.

By Stephen Edelstein - DigitalTrends.com - October 17, 2012

These days, even beautiful people go under the knife for some aesthetic augmentation, and the same is true of beautiful automobiles. Lamborghini’s Gallardo LP 560-4 Spyder has been on sale since 2008, so the company decided it was time for a refresh.

Most of the changes are skin deep, and are shared with the restyled Gallardo LP 560-4 coupe shown at last month’s Paris Motor Show. At the front, the intake is segmented by delicate-looking struts, making the car look like it either has redneck teeth or has been in a crash. There’s also a more pronounced vent in front of the wheels.

Nineteen-inch “Apollo” polished alloy wheels are also new for 2013.

At the back, the angular theme continues with a big piece of trapezoidal mesh, and taillights molded to fit. Overall, it looks like Lamborghini was trying to incorporate cues from its Sesto Elemento concept and Aventador flagship, but they don’t seem to jibe with the rest of the Gallardo’s styling.

Buyers who want a new Gallardo, but don’t like the way this one looks, needn’t fret. The LP 560-4 is actually the middle of three Gallardo trim levels. The less expensive LP 550-2 (available only as a coupe) and high performance LP 570-4 Superleggera and Spyder Performante are unchanged visually.

Aside from the styling changes, the LP 560-4 Spyder remains pretty much the same. Its 5.2-liter V10 still produces 552 horsepower and 398 pound-feet of torque. Power is sent to all four wheels through Lamborghini’s “e-gear” six-speed automated manual transmission.

The LP 550-2 continues with rear-wheel drive and the option of a six-speed manual. The Superleggera and Spyder Performante still have 570 hp, and are now offered with an Edizione Tecnica package that includes a big rear spoiler, carbon ceramic brakes, and exclusive two-tone paint.

With the fresh and fierce Ferrari 458 Italia and McLaren MP4-12C nipping at its heels, what Lamborghini really needs is an all-new Gallardo. Sant Agata has been steadily updating its car over the years, but the basic chassis hasn’t been changed since the original Gallardo debuted in 2003.

Lamborghini isn’t talking about when that new Gallardo will appear, but there are rumors of a 2013 Frankfurt Motor Show debut, with a launch sometime in 2014.

.

Monday, October 29, 2012

Sunday, October 28, 2012

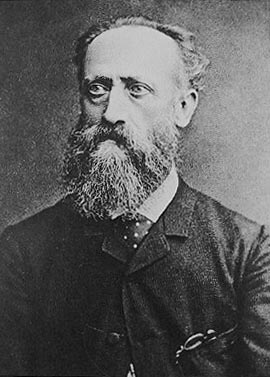

Ludovico di Varthema

Ludovico di Varthema

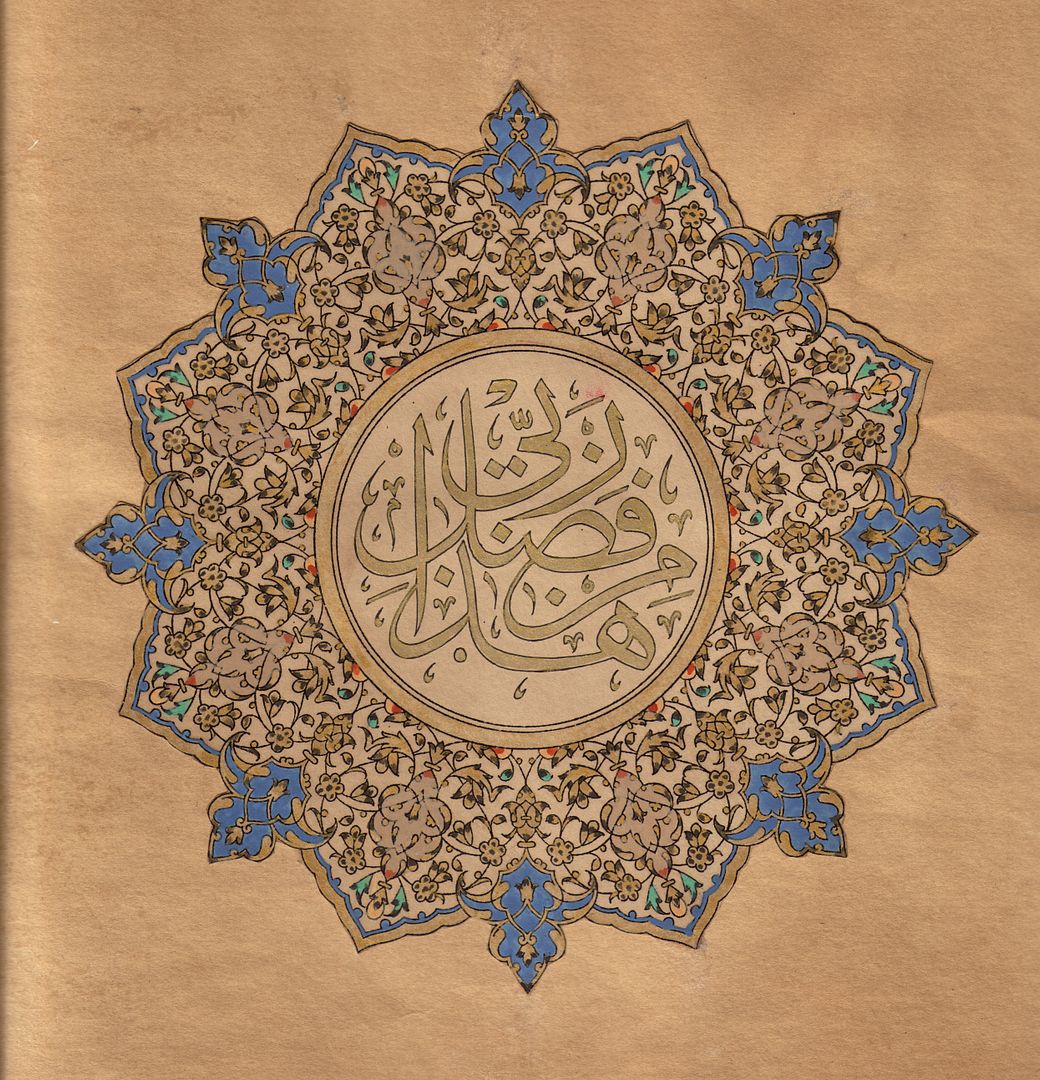

Ludovico di Varthema, also known as Barthema and Vertomannus (c. 1470-1517) was an Italian traveller, diarist and aristocrat known for being the first non-Muslim European to enter Mecca as a pilgrim. Nearly everything that is known about his life comes from his own account of his travels, Itinerario de Ludouico de Varthema Bolognese, published in Rome in 1510.

Biography

First explorations and journey to Mecca

Varthema was born in Bologna.

He was perhaps a soldier before beginning his distant journeys, which he undertook apparently from a passion for adventure, novelty and the fame which (then especially) attended successful exploration.

Varthema left Europe near the end of 1502. Early in 1503, he reached Alexandria and ascended the Nile to Cairo. From Egypt, he sailed to Beirut and thence travelled to Tripoli, Aleppo and Damascus, where he managed to get himself enrolled, under the name of Yunas (Jonah), in the Mamluk garrison. From Damascus, Varthema made the pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina as one of the Mamluk escort of the Hajj caravan (April-June 1503).

He describes the sacred cities of Islam and the chief pilgrim sites and ceremonies with remarkable accuracy, almost all his details being confirmed by later writers.

From the imprisonment to India

With the view of reaching India, he embarked at Jeddah, a city-port around 80 km west to Mecca, and sailed down the Red Sea and through the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb to Aden, where he was arrested and imprisoned as a Christian spy. By his own account, he gained his liberty after imprisonment both at Aden and Radaa because of a love affair with one on the sultanas of Yemen. Later, he made an extensive tour in south-west Arabia (visiting San‘a’), and took ship at Aden for the Persian Gulf and India. On the way, he alighted at Zeila and Berbera in Somalia. He then in early 1504 traveled to the Indian port of Diu in Gujarat, which later became famous as a Portuguese fortress.

From Diu he sailed up the Gulf of Cambay to Gogo, and thence turning back towards the Persian Gulf made Julfar (just within the entrance of the gulf), Muscat and Ormuz. From Ormuz he seems to have journeyed across Persia to Herat, returning thence south-west to Shiraz, where he entered into partnership with a Persian merchant, who accompanied him during nearly all his travels in South Asia.

After an unsuccessful attempt to reach Samarkand, the two returned to Shiraz, came down to Ormuz, and took ship for India. From the mouth of the Indus, Varthema coasted down the whole west coast of India, touching at Cambay and Chaul: at Goa, whence he made an excursion inland to Bijapur, at Cannanore, from which he again struck into the interior to visit Vijayanagar on the Tungabhadra; and at Calicut (c. 1505), where he stopped to describe the society, manners and customs of Malabar, as well as the topography and trade of the city, the court and government of its sovereign (the Zamorin), its justice, religion, navigation and military organization.

Nowhere do Varthema's accuracy and observing power show themselves more strikingly. Passing on by the backwater of Kochi, and calling at Kollam (formerly known as Quilon), he rounded Cape Comorin, and passed over to Ceylon (c. 1506). Though his stay here was brief (probably at Colombo), he learnt a good deal about the island, from which be sailed to Pulicat, slightly north of Madras, then subject to Vijayanagar. Thence he crossed over to Tenasserim in the Malay Peninsula, to Bengal, perhaps near Chittagong, at the head of the bay of Bengal, and to Pegu, in the company of his Persian friend and of two Chinese Christians whom he met at Bengal.

Sumatra, Borneo, Java and Nagapattinam

After some successful trading with the king of Pegu, Varthema and his party sailed on to Malacca, crossed over to Pider (or Pedir) in Sumatra, and thence proceeded to Banda Aceh and Monoch (one of the Moluccas), the farthest eastward points reached by the Italian traveller.

From the Moluccas, he returned westward, touched at Borneo, and there chartered a vessel for Java, the largest of islands, as his Christian companions reckoned it. Varthema notes the use of compass and chart by the native captain on the transit from Borneo to Java, and preserves a curious, more than half-mythical, reference to supposed Far Southern lands.

From Java, he crossed over to Malacca, where Varthema and his Persian ally parted from the Chinese Christians. From Malacca, he returned to the Coromandel coast, and from Nagapattinam in Coromandel he voyaged back, round Cape Comorin, to Kulam and Calicut.

Return to Europe

Varthema was now anxious to resume Christianity and return to Europe. After some time he succeeded in deserting to the Portuguese garrison at Cannanore (early in 1506). He fought for the Portuguese in various engagements, and was knighted by the viceroy Francisco de Almeida, the navigator Tristão da Cunha being his sponsor.

For a year and a half, Varthema acted as Portuguese factor at Kochi, and on the 6th of December 1507 he finally left India for Europe by the Cape route. Sailing from Cannanore, Varthema apparently struck Africa about Malindi, and (probably) coasting by Mombasa and Kilwa arrived at Mozambique, where he noticed the Portuguese fortress then building, and described with his usual accuracy the Negroes of the mainland.

Beyond the Cape of Good Hope he encountered furious storms, but arrived safely in Lisbon after sighting St Helena and Ascension Island and touching at the Azores. In Portugal the king received him cordially, kept him some days at court to learn about India, and confirmed the knighthood conferred by d'Almeida.

Legacy

His narrative finally brings him to Rome, where he takes leave of the reader. As Richard Francis Burton said in his book The Pilgrimage to Al-Medinah and Meccah:

For correctness of observation and readiness of wit Varthema stands in the foremost rank of the old Oriental travellers. In Arabia and in the Indian archipelago east of Java he is (for Europe and Christendom) a real discoverer. Even where passing over ground traversed by earlier European explorers, his keen intelligence frequently adds valuable original notes on peoples, manners, customs, laws, religions, products, trade, methods of war.

Varthema's work (Itinerario de Ludouico de Varthema Bolognese) was first published in Italian at Rome in 1510. Other Italian editions appeared at Rome, 1517, at Venice, 1518, 1535, 1563, 1589, &c., at Milan, 1519, 1523, 1525. Latin translations appeared at Milan, 1511 (by Archangelus Madrignanus); and at Nuremberg, 1610.

Notes

Thomas Suárez (1999). Early mapping of Southeast Asia. Tuttle Publishing. p. 79. ISBN 978-962-593-470-9. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Itinerary of Ludovico Di Varthema of Bologna from 1502 to 1508. By Lodovico de Varthema, John Winter Jones, Richard Carnac Temple. Contributor Lodovico de Varthema, John Winter Jones, Richard Carnac Temple. Published by Asian Educational Services, 1997. ISBN 81-206-1269-8, ISBN 978-81-206-1269-3. 121 pages.

The Travels of Ludovico di Varthema in Egypt, Syria, Arabia Deserta and Arabia Felix, in Persia, India, and Ethiopia, A.D. 1503 to 1508. By Lodovico de Varthema; Edited by George Percy Badger; Translated by John Winter Jones. Originally published by the Hakluyt Society, London in 1863. Reprint by Adamant Media Corporation, 2001. ISBN 1-4021-9553-2, ISBN 978-1-4021-9553-2.

The travels of Ludovico di Varthema in Egypt, Syria, Arabia Deserta and Arabia Felix, in Persia, India, and Ethiopia, A.D. 1503 to 1508 (1863). Various formats

.

Ludovico di Varthema, also known as Barthema and Vertomannus (c. 1470-1517) was an Italian traveller, diarist and aristocrat known for being the first non-Muslim European to enter Mecca as a pilgrim. Nearly everything that is known about his life comes from his own account of his travels, Itinerario de Ludouico de Varthema Bolognese, published in Rome in 1510.

Biography

First explorations and journey to Mecca

Varthema was born in Bologna.

He was perhaps a soldier before beginning his distant journeys, which he undertook apparently from a passion for adventure, novelty and the fame which (then especially) attended successful exploration.

Varthema left Europe near the end of 1502. Early in 1503, he reached Alexandria and ascended the Nile to Cairo. From Egypt, he sailed to Beirut and thence travelled to Tripoli, Aleppo and Damascus, where he managed to get himself enrolled, under the name of Yunas (Jonah), in the Mamluk garrison. From Damascus, Varthema made the pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina as one of the Mamluk escort of the Hajj caravan (April-June 1503).

He describes the sacred cities of Islam and the chief pilgrim sites and ceremonies with remarkable accuracy, almost all his details being confirmed by later writers.

From the imprisonment to India

With the view of reaching India, he embarked at Jeddah, a city-port around 80 km west to Mecca, and sailed down the Red Sea and through the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb to Aden, where he was arrested and imprisoned as a Christian spy. By his own account, he gained his liberty after imprisonment both at Aden and Radaa because of a love affair with one on the sultanas of Yemen. Later, he made an extensive tour in south-west Arabia (visiting San‘a’), and took ship at Aden for the Persian Gulf and India. On the way, he alighted at Zeila and Berbera in Somalia. He then in early 1504 traveled to the Indian port of Diu in Gujarat, which later became famous as a Portuguese fortress.

From Diu he sailed up the Gulf of Cambay to Gogo, and thence turning back towards the Persian Gulf made Julfar (just within the entrance of the gulf), Muscat and Ormuz. From Ormuz he seems to have journeyed across Persia to Herat, returning thence south-west to Shiraz, where he entered into partnership with a Persian merchant, who accompanied him during nearly all his travels in South Asia.

After an unsuccessful attempt to reach Samarkand, the two returned to Shiraz, came down to Ormuz, and took ship for India. From the mouth of the Indus, Varthema coasted down the whole west coast of India, touching at Cambay and Chaul: at Goa, whence he made an excursion inland to Bijapur, at Cannanore, from which he again struck into the interior to visit Vijayanagar on the Tungabhadra; and at Calicut (c. 1505), where he stopped to describe the society, manners and customs of Malabar, as well as the topography and trade of the city, the court and government of its sovereign (the Zamorin), its justice, religion, navigation and military organization.

Nowhere do Varthema's accuracy and observing power show themselves more strikingly. Passing on by the backwater of Kochi, and calling at Kollam (formerly known as Quilon), he rounded Cape Comorin, and passed over to Ceylon (c. 1506). Though his stay here was brief (probably at Colombo), he learnt a good deal about the island, from which be sailed to Pulicat, slightly north of Madras, then subject to Vijayanagar. Thence he crossed over to Tenasserim in the Malay Peninsula, to Bengal, perhaps near Chittagong, at the head of the bay of Bengal, and to Pegu, in the company of his Persian friend and of two Chinese Christians whom he met at Bengal.

Sumatra, Borneo, Java and Nagapattinam

After some successful trading with the king of Pegu, Varthema and his party sailed on to Malacca, crossed over to Pider (or Pedir) in Sumatra, and thence proceeded to Banda Aceh and Monoch (one of the Moluccas), the farthest eastward points reached by the Italian traveller.

From the Moluccas, he returned westward, touched at Borneo, and there chartered a vessel for Java, the largest of islands, as his Christian companions reckoned it. Varthema notes the use of compass and chart by the native captain on the transit from Borneo to Java, and preserves a curious, more than half-mythical, reference to supposed Far Southern lands.

From Java, he crossed over to Malacca, where Varthema and his Persian ally parted from the Chinese Christians. From Malacca, he returned to the Coromandel coast, and from Nagapattinam in Coromandel he voyaged back, round Cape Comorin, to Kulam and Calicut.

Return to Europe

Varthema was now anxious to resume Christianity and return to Europe. After some time he succeeded in deserting to the Portuguese garrison at Cannanore (early in 1506). He fought for the Portuguese in various engagements, and was knighted by the viceroy Francisco de Almeida, the navigator Tristão da Cunha being his sponsor.

For a year and a half, Varthema acted as Portuguese factor at Kochi, and on the 6th of December 1507 he finally left India for Europe by the Cape route. Sailing from Cannanore, Varthema apparently struck Africa about Malindi, and (probably) coasting by Mombasa and Kilwa arrived at Mozambique, where he noticed the Portuguese fortress then building, and described with his usual accuracy the Negroes of the mainland.

Beyond the Cape of Good Hope he encountered furious storms, but arrived safely in Lisbon after sighting St Helena and Ascension Island and touching at the Azores. In Portugal the king received him cordially, kept him some days at court to learn about India, and confirmed the knighthood conferred by d'Almeida.

Legacy

His narrative finally brings him to Rome, where he takes leave of the reader. As Richard Francis Burton said in his book The Pilgrimage to Al-Medinah and Meccah:

For correctness of observation and readiness of wit Varthema stands in the foremost rank of the old Oriental travellers. In Arabia and in the Indian archipelago east of Java he is (for Europe and Christendom) a real discoverer. Even where passing over ground traversed by earlier European explorers, his keen intelligence frequently adds valuable original notes on peoples, manners, customs, laws, religions, products, trade, methods of war.

Varthema's work (Itinerario de Ludouico de Varthema Bolognese) was first published in Italian at Rome in 1510. Other Italian editions appeared at Rome, 1517, at Venice, 1518, 1535, 1563, 1589, &c., at Milan, 1519, 1523, 1525. Latin translations appeared at Milan, 1511 (by Archangelus Madrignanus); and at Nuremberg, 1610.

Notes

Thomas Suárez (1999). Early mapping of Southeast Asia. Tuttle Publishing. p. 79. ISBN 978-962-593-470-9. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Itinerary of Ludovico Di Varthema of Bologna from 1502 to 1508. By Lodovico de Varthema, John Winter Jones, Richard Carnac Temple. Contributor Lodovico de Varthema, John Winter Jones, Richard Carnac Temple. Published by Asian Educational Services, 1997. ISBN 81-206-1269-8, ISBN 978-81-206-1269-3. 121 pages.

The Travels of Ludovico di Varthema in Egypt, Syria, Arabia Deserta and Arabia Felix, in Persia, India, and Ethiopia, A.D. 1503 to 1508. By Lodovico de Varthema; Edited by George Percy Badger; Translated by John Winter Jones. Originally published by the Hakluyt Society, London in 1863. Reprint by Adamant Media Corporation, 2001. ISBN 1-4021-9553-2, ISBN 978-1-4021-9553-2.

The travels of Ludovico di Varthema in Egypt, Syria, Arabia Deserta and Arabia Felix, in Persia, India, and Ethiopia, A.D. 1503 to 1508 (1863). Various formats

.

Saturday, October 27, 2012

Old Roman Catholic Chant - Dixit Dominus Domino meo

Old Roman Catholic Chant - Dixit Dominus Domino meo

Dixit Dominus Domino meo: Sede a dextris meis, donec ponam inimicos tuos scabellum pedum tuorum.

The Lord said unto my Lord: Sit thou on my right hand, until I make thine enemies thy foot-stool.

.

Friday, October 26, 2012

A Journey Through Early Christian Rome

A Journey Through Early Christian Rome

Based on the image album from LiveScience.com entitled 'In Photos: A Journey Through Early Christian Rome' by Owen Jarus (9-30-11). The rise of early Christianity.

http://www.livescience.com/16318-photos-early-christian-rome-catacombs-artifacts.html

[Music: 'Lacrimosa Dies' by Atrium Animae]

.

Labels:

ancient history,

Christian Rome,

Christianity,

religion

Thursday, October 25, 2012

Spot where Julius Caesar was stabbed discovered

Spot where Julius Caesar was stabbed discovered [see image]

Concrete structure believed to mark location of Roman ruler's killing

By Stephanie Pappas - Senior writer - MSNBC - October 11, 2012

Archaeologists believe they have found the first physical evidence of the spot where Julius Caesar died, according to a new Spanish National Research Council report.

Caesar, the head of the Roman Republic, was stabbed to death by a group of rival Roman senators on March 15, 44 B.C., the Ides of March. The assassination is well-covered in classical texts, but until now, researchers had no archaeological evidence of the place where it happened.

Now, archaeologists have unearthed a concrete structure nearly 10 feet wide and 6.5 feet tall that may have been erected by Augustus, Julius Caesar's successor, to condemn the assassination. The structure is at the base of the Curia, or Theater, of Pompey, the spot where classical writers reported the stabbing took place.

"We always knew that Julius Caesar was killed in the Curia of Pompey on March 15th 44 B.C. because the classical texts pass on so, but so far no material evidence of this fact, so often depicted in historicist painting and cinema, had been recovered," Antonio Monterroso, a researcher at the Spanish National Research Council, said in a statement.

Classical texts also say that years after the assassination, the Curia was closed and turned into a memorial chapel for Caesar. The researchers are studying this building along with another monument in the same complex, the Portico of the Hundred Columns, or Hecatostylon; they are looking for links between the archaeology of the assassination and what has been portrayed in art.

"It is very attractive, in a civic and citizen sense, that thousands of people today take the bus and the tram right next to the place where Julius Caesar was stabbed 2,056 years ago," Monterroso said.

.

Concrete structure believed to mark location of Roman ruler's killing

By Stephanie Pappas - Senior writer - MSNBC - October 11, 2012

Archaeologists believe they have found the first physical evidence of the spot where Julius Caesar died, according to a new Spanish National Research Council report.

Caesar, the head of the Roman Republic, was stabbed to death by a group of rival Roman senators on March 15, 44 B.C., the Ides of March. The assassination is well-covered in classical texts, but until now, researchers had no archaeological evidence of the place where it happened.

Now, archaeologists have unearthed a concrete structure nearly 10 feet wide and 6.5 feet tall that may have been erected by Augustus, Julius Caesar's successor, to condemn the assassination. The structure is at the base of the Curia, or Theater, of Pompey, the spot where classical writers reported the stabbing took place.

"We always knew that Julius Caesar was killed in the Curia of Pompey on March 15th 44 B.C. because the classical texts pass on so, but so far no material evidence of this fact, so often depicted in historicist painting and cinema, had been recovered," Antonio Monterroso, a researcher at the Spanish National Research Council, said in a statement.

Classical texts also say that years after the assassination, the Curia was closed and turned into a memorial chapel for Caesar. The researchers are studying this building along with another monument in the same complex, the Portico of the Hundred Columns, or Hecatostylon; they are looking for links between the archaeology of the assassination and what has been portrayed in art.

"It is very attractive, in a civic and citizen sense, that thousands of people today take the bus and the tram right next to the place where Julius Caesar was stabbed 2,056 years ago," Monterroso said.

.

Labels:

ancient history,

ancient Rome,

archaeology,

Caesar Augustus,

Julius Caesar,

Pompey,

Roman,

Roman Empire,

Romans

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

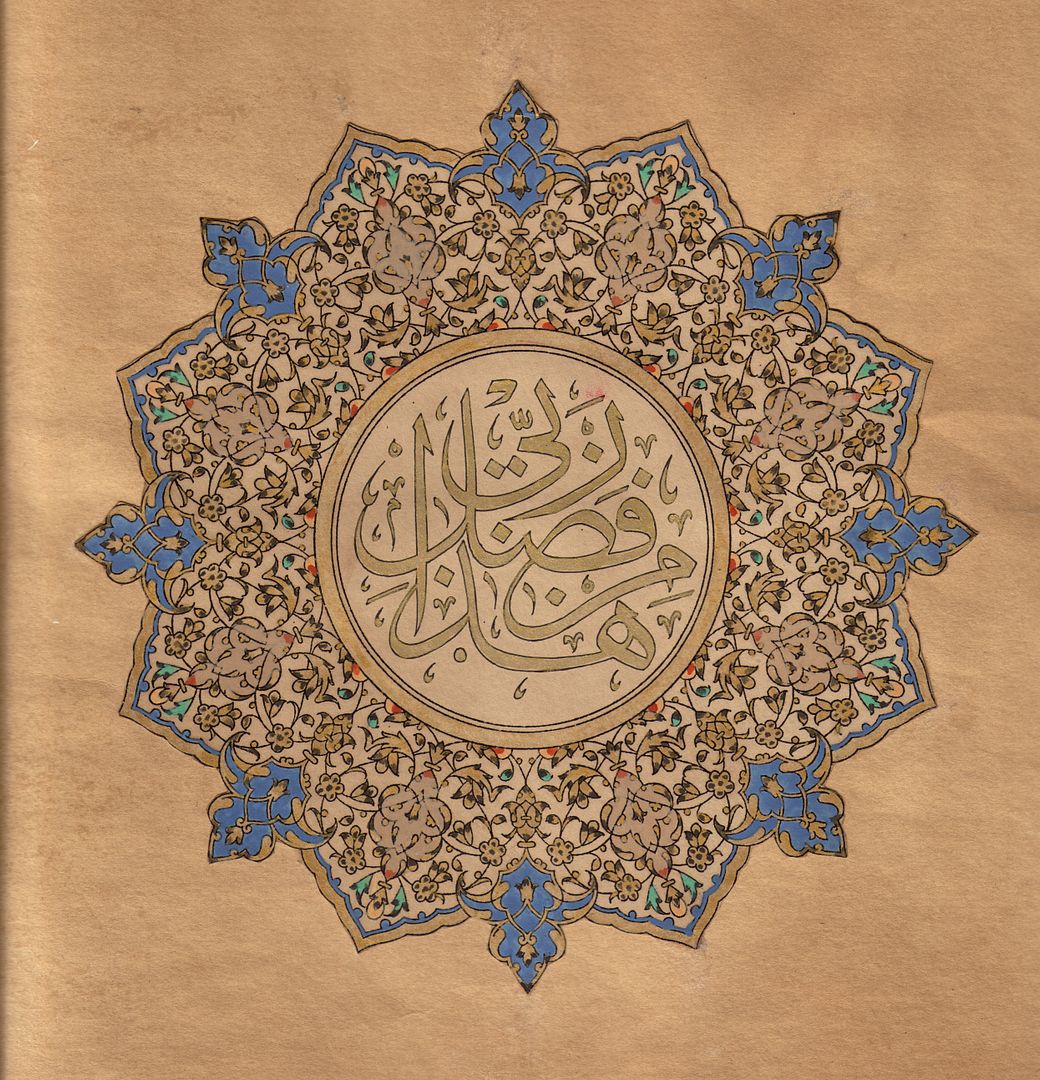

A couple of infamous rifles

I thought I would combine two rather infamous rifles into one entry. If nothing else, they both have a long and interesting history: The Carcano bolt-action rifles and carbines; and the Martini-Henry breech-loading single-shot lever-actuated rifle. Rather then copy a lot of tedious text, filled with gun jargon, I will just give a short summary of each. This is one of those subjects which tie into a lot of other subjects. Perhaps we can look at that vast history more in-depth some other time.

I thought I would combine two rather infamous rifles into one entry. If nothing else, they both have a long and interesting history: The Carcano bolt-action rifles and carbines; and the Martini-Henry breech-loading single-shot lever-actuated rifle. Rather then copy a lot of tedious text, filled with gun jargon, I will just give a short summary of each. This is one of those subjects which tie into a lot of other subjects. Perhaps we can look at that vast history more in-depth some other time.Carcano

This rifle--actually it was a series--is best known as the rifle which some believe was used to assassinate President Kennedy. It's regarded as being of relatively poor quality; but was attractive due to it's affordability. Incredibly, it was the official rifle for the Italian army from 1891 to 1981. To a gun enthusiast, it was "a piece of junk," but that's somewhat of an exaggeration I think. It was viable; a killer.

Wikipedia: Carcano is the frequently used name for a series of Italian bolt-action military rifles and carbines. Introduced in 1891, this rifle was chambered for the rimless 6.5×52mm Mannlicher-Carcano Cartuccia Modello 1895 cartridge. It was developed by the chief technician Salvatore Carcano at the Turin Army Arsenal in 1890 and called the Model 91 (M91). Successively replacing the previous Vetterli-Vitali rifles and carbines in 10.35×47mmR, it was produced from 1892 to 1945. The M91 was used in both rifle and carbine form by most Italian troops during the First World War and by Italian and some German forces during Second World War. The rifle was also used during the Winter War by Finland, and again by regular and irregular forces in Syria, Libya, Tunisia, and Algeria during various postwar conflicts in those countries.

The Type I Carcano rifle was produced by Italy for the Japanese Empire prior to World War II. After the invasion of China, all Arisaka production was required for use of the Imperial Army, so the Imperial Navy contracted with Italy for this weapon in 1937. The Type I is based on the Type 38 rifle and utilizes a Carcano action, but retains the Arisaka/Mauser type 5-round box magazine. The Type I was utilized primarily by Japanese Imperial Naval Forces and was chambered for the Japanese 6.5×50mm Arisaka cartridge. Approximately 60,000 Type I rifles were produced by Italian arsenals for Japan.

Wars fought with Carcano rifles:

Mahdist War,

First Italo-Ethiopian War,

Boxer Rebellion,

Italo-Turkish War,

World War I,

Second Italo-Abyssinian War,

Winter War,

World War II,

Libyan civil war

Users of Carcano rifles:

Albania

Bulgaria Kingdom of Bulgaria

Empire of Japan

Finland

Italy

Italy Kingdom of Italy (1861-1946)

Italian Social Republic

Nazi Germany

Libya National Liberation Army (Libya)

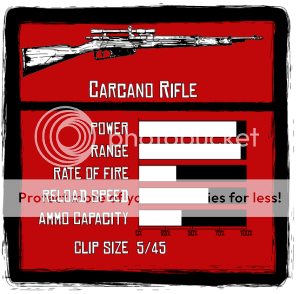

Martini-Henry

Martini-HenryThe Martini-Henry rifle is best known for it's use by the British Empire for several decades during their imperial wars. It was a heavy-duty, single-shot rifle, effective at long range, with a bayonet. In other words, truly a "hand-held cannon." Think 'Mutiny on the Bounty' for more of a historical perspective. The Martini-Henry mechanism was invented by American Henry O. Peabody in Boston in 1862, and later perfected by Swiss Friedrich von Martini in 1871, after being "combined with the polygonal barrel rifling designed by Scotsman Alexander Henry." Martini-Henrys have floated around the world long afterwards; and are still being used in some corners of the world over 120 years after the last one was produced.

Wikipedia: The Martini-Henry was a breech-loading single-shot lever-actuated rifle adopted by the British Army, combining the dropping-block action first developed by Henry O. Peabody (in his Peabody rifle) and improved by the Swiss designer Friedrich von Martini, whose work in bringing the cocking and striker mechanism all within the receiver greatly improved the operation of the rifle, which new iteration was combined with the polygonal barrel rifling designed by Scotsman Alexander Henry. It first entered service in 1871, eventually replacing the Snider-Enfield, a muzzle-loader conversion to the cartridge system. Martini-Henry variants were used throughout the British Empire for 30 years. Though the Snider was the first breechloader firing a metallic cartridge in regular British service, the Martini was designed from the outset as a breechloader and was both faster firing and had a longer range.

Wikipedia: The Martini-Henry was a breech-loading single-shot lever-actuated rifle adopted by the British Army, combining the dropping-block action first developed by Henry O. Peabody (in his Peabody rifle) and improved by the Swiss designer Friedrich von Martini, whose work in bringing the cocking and striker mechanism all within the receiver greatly improved the operation of the rifle, which new iteration was combined with the polygonal barrel rifling designed by Scotsman Alexander Henry. It first entered service in 1871, eventually replacing the Snider-Enfield, a muzzle-loader conversion to the cartridge system. Martini-Henry variants were used throughout the British Empire for 30 years. Though the Snider was the first breechloader firing a metallic cartridge in regular British service, the Martini was designed from the outset as a breechloader and was both faster firing and had a longer range.There are four classes of the Martini-Henry rifle: Mark I (released in June 1871), Mark II, Mark III, and Mark IV. There was also an 1877 carbine version with variations that included a Garrison Artillery Carbine, an Artillery Carbine (Mark I, Mark II, and Mark III), and smaller versions designed as training rifles for military cadets. The Mark IV Martini-Henry rifle ended production in the year 1889, but remained in service throughout the British Empire until the end of the First World War. It was seen in use by some Afghan tribesmen as late as the Soviet invasion. Early in 2010 and 2011, United States Marines recovered at least three from various Taliban weapons caches in Marjah. In April 2011, another Martini-Henry rifle was found near Orgun in Paktika Province by United States Army's 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault).

The Martini-Henry was copied on a large scale by North-West Frontier Province gunsmiths. Their weapons were of a poorer quality than those made by Royal Small Arms Factory, Enfield, but accurate down to the proof markings. The chief manufacturers were the Adam Khel Afridi, who lived around the Khyber Pass. The British called such weapons, "Pass made rifles."

Wars fought with Martini-Henry rifles:

British colonial wars

Second Anglo-Afghan War

Anglo-Zulu War

First Boer War

Users of Martini-Henry rifles:

United Kingdom & Colonies

.

Labels:

Carcano rifles,

industry,

invention,

manufacturing,

Martini-Henry rifles,

military history,

weaponry

Tuesday, October 23, 2012

Visions Of Italia Northern Style

'Visions of Italia - Northern Style' was a VHS tape, produced by PBS about twenty years ago, which presents the Cisalpine landscape from the air. It is available now on DVD and Blu-ray. I remember, it was a big deal back then, and was sold for $100. Is it the most beautiful land in the world? You can decide for yourself.

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Part 6

.

Labels:

architecture,

land forms,

landscape,

Northern Italy,

the Alps

Monday, October 22, 2012

Events in Cisalpine History

I'm downsizing the main website, and I wanted to enter one item from there, for future reference. A list of a few of the greatest events or periods in Cisalpine history, in chronological order:

I'm downsizing the main website, and I wanted to enter one item from there, for future reference. A list of a few of the greatest events or periods in Cisalpine history, in chronological order:Etruscan Civilization

Villanovan Culture [Iron Age]

Cisalpine Gaul [Celto-Ligurian Culture]

Langbard Kingdom

Venetian Empire [1,000 Years]

Lombard League(s)

Battle of Legnano [May 29, 1176]

The Renaissance

Battle of Lepanto [October 7, 1571]

Cinque Giornate Revolt [March 18 to March 22, 1848]

.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)