2009 Frankfurt Auto Show

2009 Frankfurt Auto Show

2011 Ferrari 458 Italia

The Ferrari we've been waiting for.

2010 Maserati GranCabrio

The convertible version of Maserati's GranTurismo features a 433-bhp V-8 and four real seats.

2010 Lamborghini Reventon Roadster

They're going fast, and not just because fewer than 20 of these topless Lamborghinis will ever be produced.

Other Reviews

2009 Lamborghini Gallardo

The 2009 Gallardo is a 2-door, 2-passenger luxury sports car, or convertible sports car, available in two trims, the LP560-4 Coupe and the LP560-4 Spyder.

2009 Lamborghini Murcielago

The 2009 Murcielago is a 2-door, 2-passenger luxury sports car, or convertible sports car, available in two trims, the LP640 Coupe and the LP640 Roadster.

Wednesday, September 30, 2009

Super sport car reviews

Tuesday, September 29, 2009

Winnili Tribe II: Origo Gentis Langobardorum

This video is based upon Paul the Deacon's eighth century summary, located in the early chapters of his book 'History of the Lombards' ("Historia Gentis Langobardorum"), of the 'Origo Gentis Langobardorum' ("origin of the Lombard people") written in the seventh century.

ORIGO GENTIS LANGOBARDORUM

The Origo Gentis Langobardorum is a short 7th century text, detailing a legend of the origin of the Lombards, and their history up to the rule of Perctarit (672688). It is preserved in three Manuscripts of the Leges Langobardorum,

HISTORY OF THE LOMBARDS

The Historia gentis Langobardorum (history of the Lombards) is the chief work by Paul the Deacon, written in the late 8th century.

This incomplete history in six books was written after 787 and at any rate no later than 796, maybe at Montecassino. It covers the story of the Lombards from 568 to the death of King Liutprand in 747, and contains much information about the Byzantine empire, the Franks, and others. The story is told from the point of view of a Lombard patriot and is especially valuable for the relations between the Franks and the Lombards. Paul used the document called the Origo gentis Langobardorum, the Liber pontificalis, the lost history of Secundus of Trent, and the lost annals of Benevento; he made a free use of Bede, Gregory of Tours and Isidore of Seville.

LOMBARDS

The Lombards (Latin Langobardi, whence the alternative names Langobards and Longobards) were a Germanic people originally from Northern Europe who settled in the valley of the Danube and from there invaded Byzantine Italy in 568 under the leadership of Alboin. They established a Kingdom of Italy which lasted until 774, when it was conquered by the Franks. Their influence on Italian political geography is apparent in the regional appellation Lombardy.

[Note: During the first millennium A.D., Scandinavia was considered an island, and was referred to as "Scadinavia."]

Friday, September 25, 2009

Alberto da Giussano and Barbarossa - Part V: Lombard League

Lombard League (Wikipedia):

Lombard League (Wikipedia):

The Lombard League was an alliance formed around 1167, which at its apex included most of the cities of northern Italy (although its membership changed in time), including, among others, Milan, Piacenza, Cremona, Mantua, Crema, Bergamo, Brescia, Bologna, Padua, Treviso, Vicenza, Venice, Verona, Lodi, and Parma, and even some lords, such as the Marquis Malaspina and Ezzelino da Romano. The League was formed to counter the Holy Roman Empire's Frederick I, who was attempting to assert Imperial influence over Italy. Frederick claimed direct Imperial control over Italy at the Diet of Roncaglia (1158). The League had the support of Pope Alexander III, who also wished to see Imperial power in Italy decline. At the Battle of Legnano on May 29, 1176, Frederick I was defeated and, by the Peace of Venice, which took place in 1177, agreed to a six-year truce from August,1178 to 1183, until the Second Treaty of Constance, where the Italian cities agreed to remain loyal to the Empire but retained local jurisdiction over their territories.

The Lombard League was renewed several times and after 1226 regained its former prestige by countering the efforts of Frederick II to gain greater power in Italy. These efforts included the taking of Vicenza and the Battle of Cortenuova which established the reputation of the Emperor as a skillful strategist. He misjudged his strength, rejecting all Milanese peace overtures and insisting on unconditional surrender. It was a moment of grave historic importance when Frederick's hatred coloured his judgment and blocked all possibilities of a peaceful settlement. Milan and five other cities held out, and in October 1238 he had to unsuccessfully raise the siege of Brescia. Once again receiving papal support, the Lombard League effectively countered Frederick's efforts. During the 1249 siege of Parma, the Imperial camp was assaulted and taken, and in the ensuing Battle of Parma the Imperial side was routed. Frederick lost the Imperial treasure and with it any hope of maintaining the impetus of his struggle against the rebellious communes and against the pope. The League was dissolved in 1250 once Frederick died.

**************************************************

The Following paragraph is from a book called 'Modern Italian grammar: a practical guide', and clarifies and simplifies a number of things:

"When, in 1152, Frederick I, known as Redbeard, became King of Germany, he decided to suppress the rebellious City States, He Carred out five raids in Italy; in the first (1154) he suppressed the rebellion in Rome, and had himself crowned emperor; in the second he conquered Milan and with due ceremony reaffirmed the rights of the emperor (1158) in the third he besieged and destroyed Milan (1163) in the fourth he occupied Rome (1168) and in the fifth he was defeated at Legnano by the Lombard League (an alliance between the City States, set up in Pontida in1167, and supported by Pope Alexander III). For this reason he was forced to recognize the freedom of the City States, with the peace treaty of Constance (1183)."

**************************************************

The critics of Padanian identity have gone after trivial facts, to try to underscore the significance of events like the Battle of Legnano. For example, whether or not there was a specific "oath" taken at the formation of the Lombard League in Pontida, Lombardy. That's how the game is played. A people's history needs to be trivialized or absorbed and molded into what is "politically correct." For example, references to "the Italian League," or that it was "for Italian freedom" even though Italy never even existed before. If the history of other groups were to be attacked, it might be answered with calls of "bigotry" or "racism." However, if you're unfortunate enough to be "politically incorrect," then you don't receive this type of protection. You're on your own.

A perfect example of this is if we look at the War of the Sicilian Vespers. Historically, it is referred to as a struggle by the Sicilian people for Sicilian freedom, which it was. However, why is the Battle of Legnano any different? It was a war carried out by Lombardo-Venetian people for Lombardo-Venetian freedom. Why the double standard?

Thursday, September 24, 2009

Alberto da Giussano and Barbarossa - Part IV: Holy Roman Empire

What this all boils down to is that most of the northern subalpine region was conquered and under the subjugation of a powerful German imperial power called the Holy Roman Empire, or what eight centuries later the German National Socialists would refer to as the "First Reich."

What this all boils down to is that most of the northern subalpine region was conquered and under the subjugation of a powerful German imperial power called the Holy Roman Empire, or what eight centuries later the German National Socialists would refer to as the "First Reich."

Rather than take this sitting down, the city-states of the newly occupied region formed an alliance called the "Lombard League" to oppose the Germanic empire. They were literally fighting for their freedom, just as some of their ancestors had done six centuries earlier when the small Winnili tribe chose to stand and fight the powerful Vandal horde rather than accept being slaves. The odds going into this war were just as long as well.

**************************************************

Holy Roman Empire (from Wikipedia):

The Holy Roman Empire was a union of territories in Central Europe during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period under a Holy Roman Emperor. The first emperor of the Holy Roman Empire was Otto I, crowned in 962. The last was Francis II, who abdicated and dissolved the Empire in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars. It was officially known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation by 1450.

The Empire's territorial extent varied over its history, but at its peak it encompassed the Kingdom of Germany, the Kingdom of Italy and the Kingdom of Burgundy; territories embracing present-day Germany (except Southern Schleswig), Austria (except Burgenland), Liechtenstein, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, the Czech Republic, Slovenia (except Prekmurje), as well as significant parts of modern France (mainly Artois, Alsace, Franche-Comté, Savoie and Lorraine), Italy (mainly Lombardy, Piedmont, Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, and South Tyrol), and present-day Poland (mainly Silesia, Pomerania, and Neumark). For much of its history the Empire consisted of hundreds of smaller sub-units, principalities, duchies, counties, Free Imperial Cities, as well as other domains. Despite its name, for much of its history the Empire did not include Rome within its borders.

Holy Roman Emperor (from Wikipedia):

The Holy Roman Emperor is a term used by historians to denote a Middle Ages ruler, who as German King had in addition received the title of "Emperor of the Romans" from the Pope of the Holy Roman Church, and after the 16th century, the elected monarch governing the Holy Roman Empire, a Central European union of territories in existence during the Medieval and the Early Modern period. Charlemagne of the Carolingian Dynasty was the first to receive papal coronation as Emperor of the Romans. Charles V was the last Holy Roman Emperor to be crowned by the Pope. The final Holy Roman Emperor-elect, Francis II, abdicated in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars that saw the Empire's final dissolution.

The standard designation of the Holy Roman Emperor was "August Emperor of the Romans." When Charlemagne was crowned in 800, his was styled as "most serene Augustus, crowned by God, great and pacific emperor, governing the Roman Empire," thus constituting the elements of "Holy" and "Roman" in the imperial title. The word Holy had never been used as part of that title in official documents. The word Roman was a reflection of the translatio imperii (transfer of rule) principle that regarded the (Germanic) Holy Roman Emperors as the inheritors of the title of Emperor of the Western Roman Empire, a title left unclaimed in the West after the death of Julius Nepos in 480.

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

Alberto da Giussano and Barbarossa - Part III: Emperor Frederick I

Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor

Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor

Excerpts from Wikipedia:

Frederick I Barbarossa (1122 – 10 June 1190) was elected King of Germany at Frankfurt on 4 March 1152 and crowned in Aachen on 9 March, crowned King of Italy in Pavia in 1154, and finally crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Adrian IV on 18 June 1155. He was crowned King of Burgundy at Arles on 30 June 1178. The name Barbarossa came from the northern Italian cities he attempted to rule, and means "red beard."

Rise to power

Eager to restore the Empire to the position it had occupied under Charlemagne and Otto I the Great, the new king saw clearly that the restoration of order in Germany was a necessary preliminary to the enforcement of the imperial rights in Italy. Issuing a general order for peace, he made lavish concessions to the nobles. Abroad, Frederick intervened in the Danish civil war between Svend III and Valdemar I of Denmark and began negotiations with the East Roman emperor, Manuel I Comnenus.

It was probably about this time that the king obtained papal assent for the annulment of his childless marriage with Adelheid of Vohburg, on the grounds of consanguinity (his great-great-grandfather was a brother of Adela's great-great-great-grandmother, making them fourth cousins, once removed). He then made a vain effort to obtain a bride from the court of Constantinople. On his accession Frederick had communicated the news of his election to Pope Eugene III, but had neglected to ask for the papal confirmation. In March 1153, Frederick concluded the treaty of Constance with the Pope whereby, in return for his coronation, he promised to defend the papacy, to make no peace with king Roger II of Sicily or other enemies of the Church without the consent of Eugene and to help Eugene regain control of the city of Rome.

Reign and wars in Italy

Frederick undertook six expeditions into Italy. In the first he was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in Rome by Pope Adrian IV, following the suppression by Imperial forces of the republican city commune led by Arnold of Brescia. During the 1155 campaign in Rome, Frederick quickly allied forces with Pope Adrian IV to regain the city. The major opposition was led by Arnold of Brescia, a student of Abelard. Arnold was captured and hanged for treason and rebellion. Despite his unorthodox teaching concerning theology, Arnold was not charged with heresy. Frederick left Italy in the autumn of 1155 to prepare for a new and more formidable campaign.

In June 1158, Frederick set out upon his second Italian expedition, accompanied by Henry the Lion and his Saxon troops. This expedition resulted in the establishment of imperial officers in the cities of northern Italy, the revolt and capture of Milan, and the beginning of the long struggle with Pope Alexander III. In response to his excommunication by the pope in 1160, Frederick declared his support for Antipope Victor IV. Frederick attempted to convoke a joint council with King Louis of France in 1162 to decide the issue of who should be pope. Louis came near the meeting site but, when he became aware that Frederick had stacked the votes for Alexander, Louis decided not to attend the council. As a result the issue was not resolved at that time.

The political result of the struggle with Pope Alexander was that the Norman state of Sicily and Pope Alexander III formed an alliance against Frederick. Returning to Germany towards the close of 1162, Frederick prevented the escalation of conflicts between Henry the Lion from Saxony and a number of neighbouring princes who were growing weary of Henry's power, influence and territorial gains. He also severely punished the citizens of Mainz for their rebellion against Archbishop Arnold. The next visit to Italy in 1163 saw his plans for the conquest of Sicily ruined by the formation of a powerful league against him, brought together mainly by opposition to imperial taxes.

In 1164 Frederick took what are believed to be the relics of the "Biblical Magi" (the Wise Men or Three Kings) from Milan and gave them as a gift (or as loot) to the Archbishop of Cologne, Rainald of Dassel. The relics had great religious significance and could be counted upon to draw pilgrims from all over Christendom. Today they are kept in the Shrine of the Three Kings in the Cologne cathedral.

Frederick then focused on restoring peace in the Rhineland, where he organized a magnificent celebration of the canonization of Charles the Great (Charlemagne) at Aachen. In October 1166, he went once more on journey to Italy to secure the claim of his Antipope Paschal III, and the coronation of his wife Beatrice as Holy Roman Empress. This time, Henry the Lion refused to join Frederick on his Italian trip, tending instead to his own disputes with neighbors and his continuing expansion into Slavic territories in northeastern Germany. Frederick's forces achieved a great victory over the Romans at the Battle of Monte Porzio, but his campaign was stopped by the sudden outbreak of an epidemic (malaria or the plague), which threatened to destroy the Imperial army and drove the emperor as a fugitive to Germany, where he remained for the ensuing six years.

Later years

Later years

In 1174, Frederick made his fifth expedition to Italy but was opposed by the pro-papal Lombard League (now joined by Venice, Sicily and Constantinople) which had previously formed to stand against him. The cities of northern Italy had become exceedingly wealthy through trade, and represented a marked turning point in the transition from medieval feudalism. While continental feudalism had remained strong socially and economically, it was in deep political decline by the time of Frederick Barbarossa. When the northern Italian cities inflicted a defeat on Frederick, the European world was shocked that such a thing could happen. With the refusal of Henry the Lion to bring help to Italy, the campaign was a complete failure.

Frederick was able to march through Northern Italy and occupy Rome with his self-appointed Antipope Paschal III, but the Lombards rose up behind him while a severe fever crippled his army. Frederick suffered a heavy defeat at the Battle of Legnano near Milan, on 29 May 1176, where he was wounded and for some time was believed to be dead. This battle marked the turning point in Frederick's claim to empire. He had no choice other than to begin negotiations for peace with Alexander III and the Lombard League. In the Peace of Anagni in 1176, Frederick recognized Alexander III as Pope and in the Peace of Venice, 1177, Frederick and Alexander III were formally reconciled. The scene was similar to that which had occurred between Pope Gregory VII and Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor at Canossa a century earlier.

The conflict was the same as that resolved in the Concordat of Worms. Did the Holy Roman Emperor have the power to name the pope and bishops? The Investiture controversy from previous centuries had been brought to a tendentious peace with the Concordat of Worms and affirmed in the First Council of the Lateran. Now it had recurred, in a slightly different form. Frederick had to humble himself before Pope Alexander III at Venice. The Emperor acknowledged the Pope's sovereignty over the Papal States, and in return Alexander acknowledged the Emperor's overlordship of the Imperial Church. Also in the Peace of Venice, a truce was made with the Lombard cities,which took effect in August, 1178. But the grounds for a permanent peace were established only in 1183, when, in the Peace of Constance, Frederick conceded their right to freely elect town magistrates. By this move, Frederick recovered his nominal domination over Italy. This became his chief means of applying pressure on the papacy.

Frederick and the Justinian code

Because of the increase in wealth of the trading cities of northern Italy, there occurred a revival in the study of the Justinian Code. This was a Latin legal system which had become extinct in earlier centuries. Legal scholars renewed its application. It is speculated that Pope Gregory VII personally encouraged the Justinian rule of law, and possessed a copy of it. Corpus Iuris Civilis (Justinian Body of Civil Law) has been described as the greatest code of law ever devised. It envisaged the law of the state as a reflection of natural moral law, the principle of rationality in the universe. By the time Frederick assumed the throne, this legal system was well established on both sides of the Alps. He was the first to utilize the availability of the new professional class of lawyers. The Civil Law allowed Frederick to use these lawyers to administer his kingdom in a logical and consistent manner. It also provided a framework to legitimize his claim to the right to rule both Germany and northern Italy. In the old days of Henry VI and Henry V, the claim of divine right of kings had been severely undermined by the Investiture controversy. The Church had won that argument in the common man's mind. There was no divine right for the German king to also control the church by naming both bishops and popes. The institution of the Justinian code was used, perhaps unscrupulously, by Frederick to lay claim to divine powers.

In Germany, Frederick was a political realist, taking what he could and leaving the rest. In Italy, he tended to be a romantic reactionary, reveling in the antiquarian spirit of the age, exemplified by a revival of classical studies and Roman law. It was through the use of the restored Justinian code that Frederick came to view himself a the new Roman emperor. Roman law gave a rational purpose, for the existence of Frederick and his imperial ambitions. It was a counterweight to the claims of the Church to have authority because of divine revelation. The Church was opposed to Frederick for ideological reasons, not the least of which was the humanist nature found in the revival of the old Roman legal system. When Pepin the Short sought to become king of the Franks, the church needed military protection. Pepin found it convenient to make an ally of the pope. Frederick desired to put the pope aside and claim the crown of old Rome simply because he was in the likeness of the greatest emperors of the pre-Christian era. Pope Adrian IV was naturally opposed to this view and undertook a vigorous propaganda campaign which was designed to diminish Frederick and his ambition. To a large extent, this was successful.

Charismatic leader

Charismatic leader

Comparison has been made between Henry II of England and Frederick Barbarossa. Both were considered to be the greatest and most charismatic leaders of the age. Each had a rare combination of qualities which made them appear to be superhuman to their contemporaries. They possessed longevity, boundless ambition, extraordinary organizing skill, and greatness on the battlefield. They were handsome and proficient in courtly skills, without appearing effeminate or affected. Both came to the throne in the prime of manhood. Each had an element of learning, without being considered impractical intellectuals, but rather more inclined to practicality. Each found himself in the possession of new legal institutions which were put to creative use in governing. Both Henry and Frederick were viewed to be sufficiently and formally devout to the teachings of the Church, without being moved to the extremes of spirituality seen in the great saints of the twelfth century. In making final decisions, each relied solely upon their own judgment. Both were interested in gathering as much power as they could.

Frederick's charisma led to a fantastic juggling act which over a quarter of a century, restored the imperial authority in the German states. His formidable enemies defeated him on almost every side, yet, in the end, he emerged triumphant. When Frederick came to the throne, the prospects for the revival of German imperial power were extremely thin. The great German princes had increased their power and land holdings. The king had been left with only the traditional family domains and a vestige of power over the bishops and abbeys. The backwash of the Investiture controversy had left the German states in continuous turmoil. Rival states were in perpetual war. These conditions allowed Frederick to be both warrior and occasional peace-maker, both to his advantage.

**************************************************

There is a lot more information about Emperor Frederick I, or as he is more widely known "Barbarossa." He truly affected the northern subalpine nations so much, that his nickname has reigned loudly down through history. The historical record seems to show him not as much a tyrant as he was an aggressive imperialist, and one with a lot of power. Then again, in the preview for the upcoming movie 'Barbarossa', he is shown cutting off a man's ear, so maybe we need to keep this as an open question.

Of further significance to us today, is that there have been four times in history that the closely-related subalpine nations have become "one nation." First, through Etruscan civilization, which at it's peak encompassed the vast majority of the north. Second, through Gallia Cisalpina, as the Roman's called the region of the Celto-Ligurian tribal culture. Third, and the most "administratively proactive" was the Langbard Kingdom. And fourth, through the Lombard League(s).

Sunday, September 20, 2009

Alberto da Giussano and Barbarossa - Part II: Alberto da Giussano

Alberto da Giussano, a native of Lombardy, was a legendary Guelph warrior during the wars of the Lombard League against Frederick Barbarossa in 12th century. Fourteenth century Milanese chroniclers attributed him the deed of forming the "Company of Death" which defended the Carroccio of the League at the Battle of Legnano. Lega Nord uses, as it's emblem, an image inspired by the statue of him erected at Legnano in 1900.

Alberto da Giussano, a native of Lombardy, was a legendary Guelph warrior during the wars of the Lombard League against Frederick Barbarossa in 12th century. Fourteenth century Milanese chroniclers attributed him the deed of forming the "Company of Death" which defended the Carroccio of the League at the Battle of Legnano. Lega Nord uses, as it's emblem, an image inspired by the statue of him erected at Legnano in 1900.

Some anti-Northern League sources claim that some historical aspects involving da Giussano are a myth. This record does have some historical merit, but why this is even relevant anyway is a mystery to me. It's like fighting over whether or not William Wallace tied his left shoe first before the Battle of Sterling, RATHER than acknowledge the significance of the battle itself!

Alberto da Giussano seems to be the main player, along with German Emperor Fredrick I, in the upcoming Italian movie 'Barbarossa.' I think part of the significance of da Giussano, like William Wallace, was the concept of one common man standing up to an extremely powerful imperial dictator, and winning. The old American ideal of loving an underdog is exemplified here I think.

When looking at the excerpts of 'Barbarossa', it gives the appearance of a classic Italian movie. A certain passion and purity comes through it seems. I'm looking forward to it.

[8-12-10 Addition: The following link is for the Alberto da Giussano Wikipedia webpage]

Sunday, September 6, 2009

From Mercury to Wotan

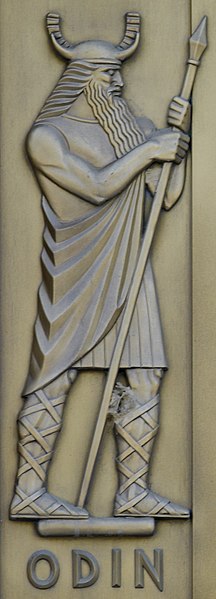

In Paul the Deacon's 'History of the Lombards', Book I - Chapter IX, the last sentence reads: "Wotan indeed, whom by adding a letter they called Godan is he who among the Romans is called Mercury, and he is worshipped by all the peoples of Germany as a god, though he is deemed to have existed, not about these times, but long before, and not in Germany, but in Greece."

In Paul the Deacon's 'History of the Lombards', Book I - Chapter IX, the last sentence reads: "Wotan indeed, whom by adding a letter they called Godan is he who among the Romans is called Mercury, and he is worshipped by all the peoples of Germany as a god, though he is deemed to have existed, not about these times, but long before, and not in Germany, but in Greece."

Was this true? Did the Romans and Greeks share a major god with the Germanic peoples, and perhaps others? If so, that would be a strong bond linking ancient Europe. It should also be noted that the Celts had an extensive mythology, and also we've begun to learn in recent years of the extensive "Slavic mythology" that existed. Staying with the original question, we might be able to start to answer some questions.

Greeks

Hermes is the Messenger of the gods in Greek mythology. An Olympian god, he is also the patron of boundaries and of the travelers who cross them, of shepherds and cowherds, of thieves and road travelers, of orators and wit, of literature and poets, of athletics, of weights and measures, of invention, of general commerce, and of the cunning of thieves and liars.

Romans

In Roman mythology, Mercury (associated with the Greek deity Hermes) was a messenger, and a god of trade, profit and commerce, the son of Maia Maiestas, also known as Ops, the Roman version of Rhea, and Jupiter.

Also according to Wikipedia: "Mercury did not appear among the numinous di indigetes of early Roman religion. Rather, he subsumed the earlier Dei Lucrii as Roman religion was syncretized with Greek religion during the time of the Roman Republic, starting around the 4th century BC. From the beginning, Mercury had essentially the same aspects as Hermes, wearing winged shoes talaria and a winged petasos, and carrying the caduceus, a herald's staff with two entwined snakes that was Apollo's gift to Hermes."

Etruscans

So, according to the above paragraph, Mercury entered the Roman religion some time after the founding of the Roman Republic. There was a break in time there. To answer that question, we again have to explore the Roman ruination of ancient Etruria. The Etruscans called the Greek god Hermes "Turms" (see chart). Well, isn't that interesting. The Etruscans worshipped this god long before Rome, and is it such a stretch to ponder as to whether or not the early Roman elite deliberately deconstructed an important Etruscan god? I have made the comparison of the Etruscans to the USA nation state, and the Romans to the Globalist American leadership. Both deconstructed much of what had been tradition in favor of internationalism.

Now we do not necessarily know if Hermes appeared in Greek mythology prior to Etruscan mythology, but we would have to assume Greece until proven otherwise. We do know that Etruria was not a colony of Greece, and was a strong nation right along with Greece, and that the "Greece then Rome" concept is largely untrue. By destroying the highly advanced Etruscan architecture, the Romans were indeed able to wipe ancient Etruria out of memory. Celts

Celts

[Left: A three-headed image of a Celtic deity, interpreted as Mercury and now believed to represent Lugus]

When they described the gods of Celtic and Germanic tribes, rather than considering them separate deities, the Romans interpreted them as local manifestations or aspects of their own gods, a cultural trait called the interpretatio Romana. Mercury in particular was reported as becoming extremely popular among the nations the Roman Empire conquered; Julius Caesar wrote of Mercury being the most popular god in Britain and Gaul, regarded as the inventor of all the arts. This is probably because in the Roman syncretism, Mercury was equated with the Celtic god Lugus, and in this aspect was commonly accompanied by the Celtic goddess Rosmerta. Although Lugus may originally have been a deity of light or the sun (though this is disputed), similar to the Roman Apollo, his importance as a god of trade and commerce made him more comparable to Mercury, and Apollo was instead equated with the Celtic deity Belenus.

Romans associated Mercury with the Germanic god Wotan, by interpretatio Romana; 1st-century Roman writer Tacitus identifies the two as being the same, and describes him as the chief god of the Germanic peoples. Julius Caesar, in a section of his "Gallic Wars" describing the customs of the German tribes, wrote "The Germans most worship Mercury," apparently identifiyng Wotan with Mercury.

In Celtic areas, Mercury was sometimes portrayed with three heads or faces, and at Tongeren, Belgium, a statuette of Mercury with three phalli was found, with the extra two protruding from his head and replacing his nose; this was probably because the number 3 was considered magical, making such statues good luck and fertility charms. The Romans also made widespread use of small statues of Mercury, probably drawing from the ancient Greek tradition of hermae markers.

Lugus was a deity apparently worshipped widely in antiquity in the Celtic-speaking world. His name is rarely directly attested in inscriptions, but his importance can be inferred from placenames and ethnonyms, and his nature and attributes are deduced from the distinctive iconography of Gallo-Roman inscriptions to Mercury, who is widely believed to have been identified with Lugus, and from the quasi-mythological narratives involving his linguistic descendants, Irish Lugh and Welsh Lleu Llaw Gyffes.

"Gaulish Mercury"

Julius Caesar in his De Bello Gallico identified six gods worshipped in Gaul, by the usual conventions of interpretatio Romana giving the names of their nearest Roman equivalents rather than their Gaulish names. He said that "Mercury" was the god most revered in Gaul, describing him as patron of trade and commerce, protector of travellers, and the inventor of all the arts. The Irish god Lug bore the epithet samildánach (skilled in all arts), which has led to the widespread identification of Caesar's Mercury as Lugus. Mercury's importance is supported by the more than 400 inscriptions into him in Roman Gaul and Britain. Such a blanket identification is optimistic – Jan de Vries[8] demonstrates the unreliability of any one-to-one concordance in the interpretatio Romana – but the available parallels are worth considering.

Ancient Germanic Peoples

Odin is considered the chief god in Norse paganism and the ruler of Asgard. Homologous with the Anglo-Saxon Wōden and the Old High German Wotan, it is descended from Proto-Germanic *Wōđinaz or *Wōđanaz. The name Odin is generally accepted as the modern translation; although, in some cases, older translations of his name may be used or preferred. His name is related to ōðr, meaning "fury, excitation", besides "mind", or "poetry". His role, like many of the Norse gods, is complex. He is considered a principal member of the Aesir (Norse Pantheon) and is associated with wisdom, war, battle, and death, and also magic, poetry, prophecy, victory, and the hunt.

Parallels between Odin and Celtic Lugus have often been pointed out: both are intellectual gods, commanding magic and poetry. Both have ravens and a spear as their attributes, and both are one-eyed. Julius Caesar (de bello Gallico, 6.17.1) mentions Mercury as the chief god of Celtic religion. A likely context of the diffusion of elements of Celtic ritual into Germanic culture is that of the Chatti, who lived at the Celtic-Germanic boundary in Hesse during the final centuries before the Common Era.

It can be concluded that various mythological figures, from different cultures, were "associated" with a counterpart. This may have been partly due to political maneuvering by Romans and others, to pacify the population. To conjoin different cultures under a unified imperial state, in the same way that early Christians, rather than try to force the abolition of a pagan holiday, just co-opted it until it more-or-less disappeared.