|

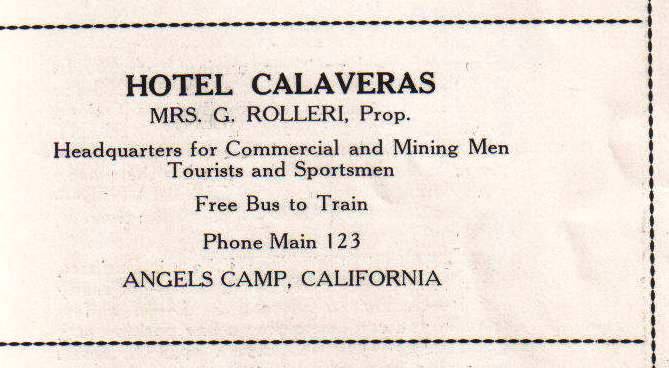

| The Calaveras Hotel, circa 1890. |

‘Grandma’ Rolleri: the Angel of Angels Camp

By Judy Georgiou - Calaveras Enterprise - June 11, 2013

The story has all the key elements of a thrilling Wild West movie with John Wayne in the cast. It includes, as with so many Westerns, the lure of riches in the Gold Rush, a spark of true love, even the capture of a dangerous outlaw. But what kind of story would it be without a fearless hero in the leading role?

The twist in this tale is that our hero is a woman. Her name: Olivia Antonini Rolleri.

The Rolleri name is certainly not foreign to Calaveras County; in fact, it’s hard to find anyone who hasn’t heard it. Rusty Rolleri of Angels Camp, wife of the late Dick Rolleri, sat at her kitchen table, a small cardboard box balanced on her lap. She opened the flaps and pulled out an old, faded photograph: a porthole into a story that is as intrinsic to Angels Camp as the gold that runs in its hills.

The black-and-white photo is of Olivia Antonini, born Aug. 1, 1844, in San Antonia de Castiglione, a small village high in the hills above the Italian Riviera. When Olivia was 16, she traveled with her mother and sister to the California foothills. They joined her father who had preceded them to Sonora, working in the mines until he had saved enough money to send for them.

Shortly after Olivia arrived, she discovered her life was about to change again. Following a traditional Italian custom, her father had already chosen a young man for her to marry. Olivia shook her head. This was a new world; she had someone else in mind. A year later, she married the dashing Italian miner Gerolamo Rolleri, whose family had lived not far from hers in Italy, although they had never met before Sonora.

Over the next 27 years,

Gerolamo mined, ran cattle and operated a ferry. With Olivia by his

side, they ran a general store and raised a family. They had 13

children: five girls and eight boys, although two died in infancy.

Over the next 27 years,

Gerolamo mined, ran cattle and operated a ferry. With Olivia by his

side, they ran a general store and raised a family. They had 13

children: five girls and eight boys, although two died in infancy.The family was happy and prospering. In fact, in 1883 their eldest son, James Jr., brought fame to the Rolleri name by helping to capture the notorious gentleman bandit, Black Bart. James Jr. was presented with an engraved rifle by Wells Fargo for his bravery.

But the story took a turn in 1888; Gerolamo died from pneumonia, leaving Olivia with 10 children to care for. The youngest child was only 1.

Olivia knew she had to find a way to provide for her family. In 1889, she purchased a small hotel in downtown Angels Camp. Although Calaveras had lost half its population between 1850-1860, like most gold mining areas in California, Angels Camp was hardly a ghost town. Its gold mines, the basis of its economy, were still going strong.

“Running the hotel was a family operation,” explained Rusty. “The girls would sweep and make beds; the boys would scrub and run errands, and later run the cattle business. She counted on her children to help. That’s how it was back then.”

Rusty dusted off another small photo and smiled at the scene: The Hotel Calaveras in 1890, Olivia at the entrance, her sons and daughters on the upstairs porch, in front of the hotel and in the horse-drawn wagon. All the girls wore long dresses and aprons; the men suspenders and hats.

Through hard work, Olivia and her family transformed the Hotel Calaveras into a thriving enterprise. The saloon had bartenders in immaculate pearl-buttoned vests; local women sipped a discreet sherry in the private parlor after shopping. The dining room – complete with crisp white tablecloths, real napkins and fresh flowers – overflowed with regulars who enjoyed a sensational Italian feast prepared by well-trained Chinese cooks using Olivia’s recipes. “Drummers” (traveling salesmen) wrote orders on wooden desks in the parlor; single men who worked the gold mines called it home.

Olivia proved to be a born entrepreneur. Over the next 20 years she expanded, purchasing three buildings, increasing the hotel capacity to 50 rooms. The rooms weren’t grand, but they were as good as might be found anywhere in the Gold Country. Although the bedrooms didn’t have heat or private baths, each room had a bowl, a pitcher of water and clean beds. Before entering the dining room, miners could shower and change on the ground floor. Room and board fees were $25 a month in the early days, and it was all-you-can eat Italian style. Olivia would even pack as many as 75 lunch pails for miners every morning.

|

| Amador County, California |

Over time, the hotel became the center of life in Angels Camp and Olivia became affectionately known as “Grandma” Rolleri. “She was full of love,” Rusty said, “and love meant sharing.”

Grandma Rolleri was a generous humanitarian, befriending those less fortunate. If there was an empty bed or food in the kitchen, she simply couldn’t turn anyone away even if they couldn’t afford to pay. “She took everyone under her wing and everyone loved her,” Rusty added. “She was an inspiration. She never met anyone she didn’t like.”

“She always wore a long white apron with pockets. She put any tips she received in the pockets and gave them to the church for the poor. Dick, who lived in the hotel as a young boy, adored her,” Rusty recalled. “He remembered rocking with her on the second story porch that ran the length of the hotel. She’d talk to him in Italian. I’m not sure he even understood anything she said, but it didn’t matter. He loved her.”

Her reputation for kindness spread across Calaveras, California and even around the world. Her Chinese cooks returned home to retire and spread stories of the Italian woman who cared for them in a strange country.

On June 10, 1927, Grandma Rolleri died at the age of 83. She’s buried, alongside members of her family, in the Altaville family cemetery.

Between 1930-1945, a Madison Avenue company produced a radio and television anthology called “Death Valley Days,” featuring true stories of the American West. An episode that ran July 1, 1938, was titled “Grandma Rolleri.” The announcer asked the Old Ranger where Angels Camp got its name. He replied, “Well, there’s been angels that’s lived there… an’ my story tonight is about one of ’em.”

Rusty replaced the worn photos in the cardboard box and closed the flaps. “No one was ever turned away from Grandma’s door; color or creed meant nothing to her,” she said. “All people were her friends, and she was a friend to all people.”

Judy Georgiou is a freelance writer from West Point. She can be reached at jlgeorgiou@gmail.com.

.